The comprehension structure is one of the most iconic utilities in Python.

Many of you may already be familiar with list comprehensions but did you know there are actually 4 types of comprehensions? We’ll review list comprehensions and introduce the others that you may have not seen before. For each type I will present the iterative forms you may currently know and how to consider converting them into comprehensions.

Why Use Comprehensions?

Before we step into the material, let’s consider why you’d want to use comprehensions in the first place. Generally speaking all types of comprehensions the benefits are as follows.

- Requires fewer lines of code to express the same concepts

- Transforms iterative code into a more readable one-liner

- More time and space efficient than the iterative (for loop) variant

List Comprehensions

List comprehensions are the most common comprehensions, but to better understand how they work let’s first look at how we can accomplish the same utility with a loop.

List Creation via Loops

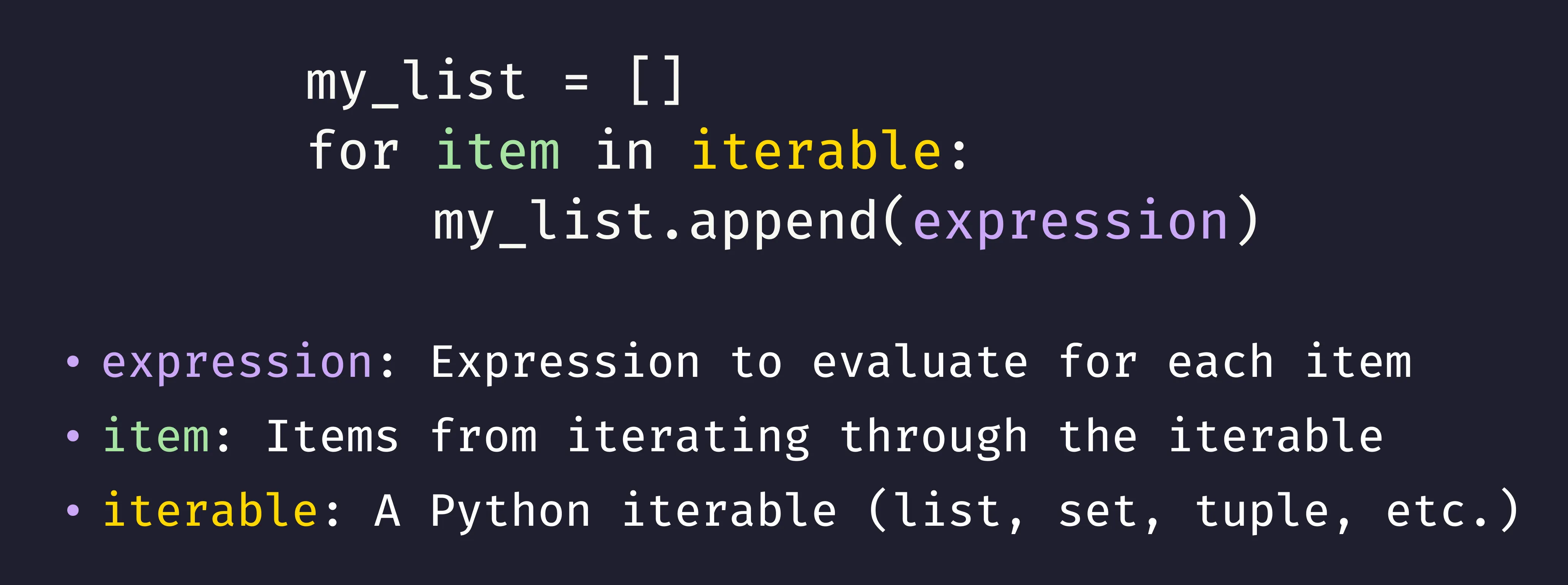

Consider how we might construct a basic list comprised of elements of a Python iterable when each item is passed through an expression. The general structure is something you may have already done before with a list initialization and a for loop.

A Python iterable is an object that returns its members one at a time. Some iterables that you may have already used are lists, sets, and tuples.

This structure is fine but as we add other bits of utility it can become harder to read the code while also adding additional overhead. Let’s turn this into a comprehension instead.

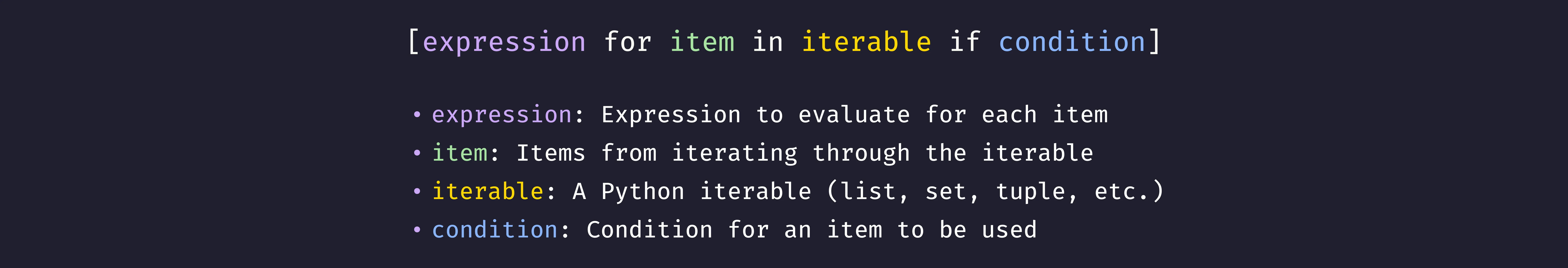

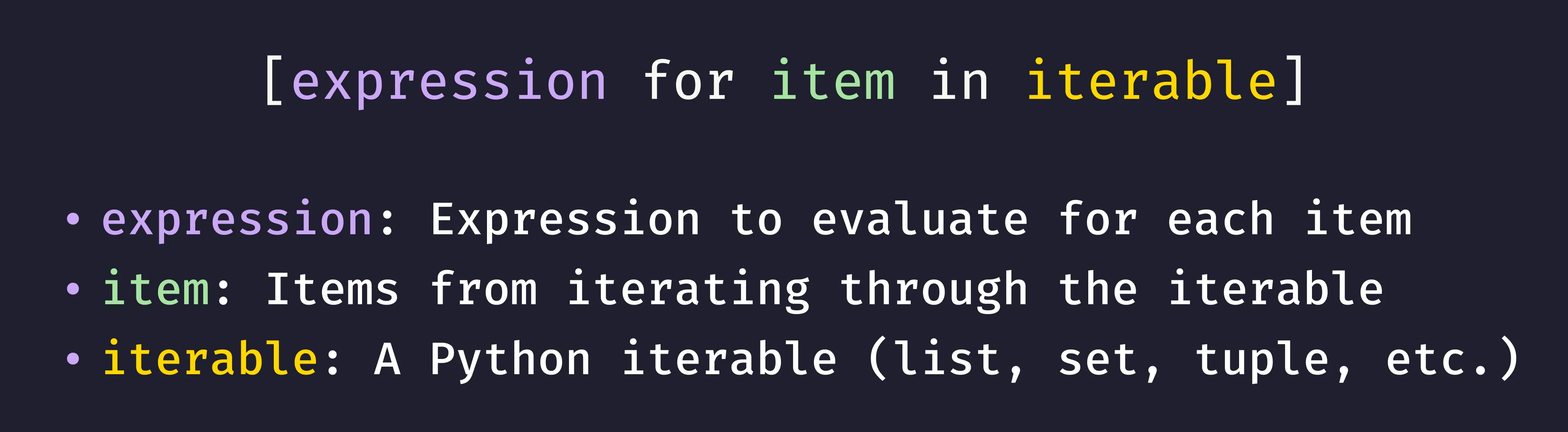

List Creation via Comprehension

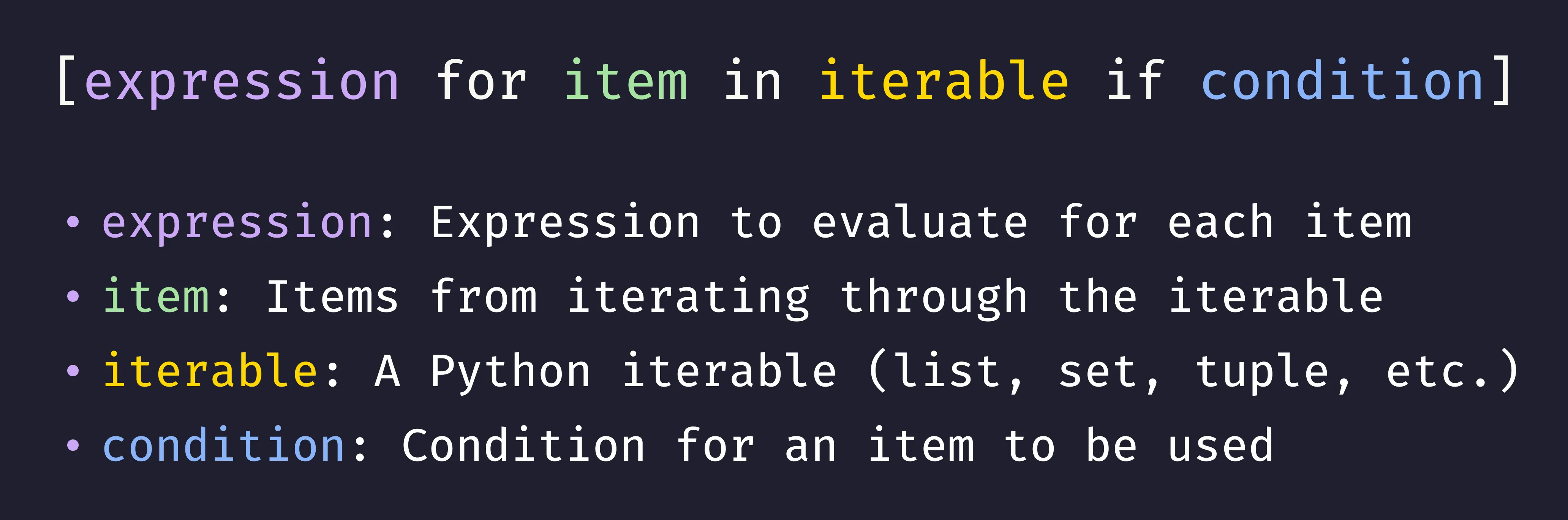

For a list comprehension, we wrap part of our prior for loop does code within brackets to produce a resultant list that is equivalent to the list from before.

The list comprehension handles the list initialization and appending and reduces the code to just what are we iterating over and what are we doing to each of the elements.

Adding a Condition

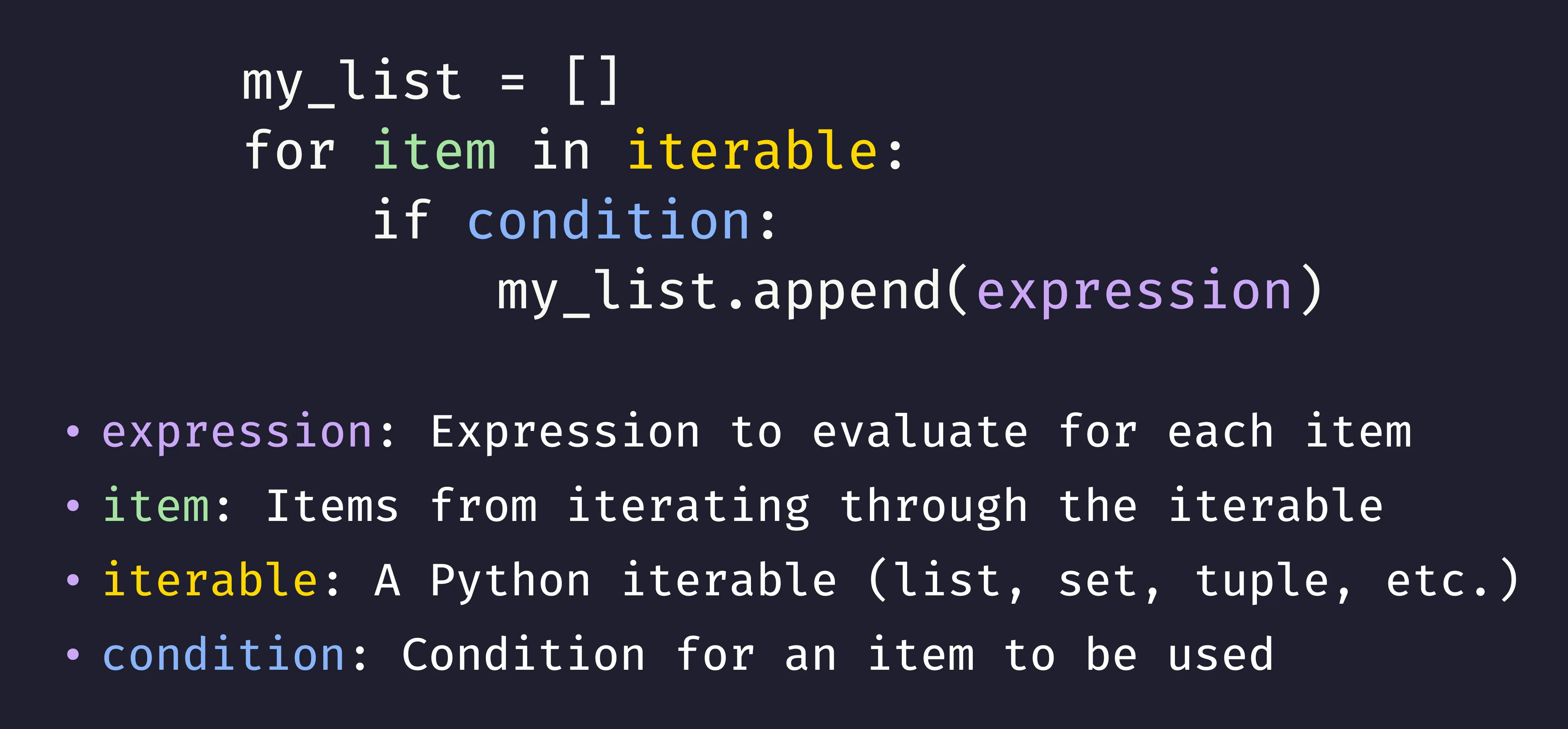

When iterating through a collection of items, we often only want to produce a list where items pass a condition. We extend the prior loop to have a condition quite easily.

It’s pretty simple to also extend this condition format into our comprehensions.

From now on I will just be including a condition in the structures of later iterations.

They are always optional and depend on what you need!

Reducing to a Comprehension

One trend you may have noticed is that the parts of the statement that make up the comprehension after the expression are just the line by line read of our iterative variant.

# Iterative Variant

my_list = []

for item in iterable:

if condition:

my_list.append(expression)If you were to unravel the highlighted lines of the above, you’d get the equivalent comprehension. This mental model is helpful for converting iterative code.

Aside On Nested Comprehensions

Although nested comprehensions exist to emulate nested loops, I would highly recommend you stay away from them. In the same mantra of generally avoiding nested loops, I find that the intense one-liners you can achieve through nested comprehensions stray away from the core principles of readability and simplicity that we strive so hard for.

Examples

Let’s look at examples of how we can write the tasks both as loops and comprehensions.

Squaring Numbers in an Iterable

We’re given an iterable of numbers and we’re asked to create a list of the squares.

# List of Numbers numbers = [-2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] # Loop Variant my_list = [] for num in numbers: my_list.append(num ** 2) print(my_list) # Comprehension Variant my_list = [num ** 2 for num in numbers] print(my_list)

output[4, 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25] [4, 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

We get the exact same result! Let’s break down the important parts in the structure.

- Iterable: The iterable is the list

numbers - Item: Each number we retrieve out of the list is our item

- Expression: The expression is merely the squaring of the number

num ** 2

Flooring Floats

We’re given a different iterable full of floating point numbers and we wish to use floor to round down to the nearest integer, but only if the numbers are positive.

# Importing the floor function from math import floor # List of Numbers numbers = [0.15, 3.14, -5.8, 11.2] # Loop Variant my_list = [] for num in numbers: if num >= 0: my_list.append(floor(num)) print(my_list) # Comprehension Variant my_list = [floor(num) for num in numbers if num >= 0] print(my_list)

output[0, 3, 11] [0, 3, 11]

We can call functions or really execute any bit of code as the expression! Often I will write a larger function and call that function from a simple comprehension.

Capitalizing Names

Given a list of names, create a new list where every name is capitalized.

# List of Names names = ["james", "charlotte", "Patrick", "elaine"] # Loop Variant my_list = [] for name in names: my_list.append(name.capitalize()) print(my_list) # Comprehension Variant my_list = [name.capitalize() for name in names] print(my_list)

output['James', 'Charlotte', 'Patrick', 'Elaine'] ['James', 'Charlotte', 'Patrick', 'Elaine']

I hope at this point you have a decent grasp of how simple list comprehensions work. For later comprehensions we’ll build off this so make sure this section makes sense!

Generator Comprehensions

You may not believe me, but you already grasp most of the information to understand generator comprehensions, even if they sound unfamiliar! Generator comprehensions are extremely similar to list comprehensions with some changes that can be very useful.

What’s a Generator?

Generators don’t store all the results but just pass them one at a time when you call the generator. This is great for saving memory but not great if you want to save the resultant list.

I could write a whole blog post on just generators, but the important part to understand is that generators are functions that you can write that act like iterators.

Let’s work through a simple example and see why generators are AWESOME. Let’s consider our prior example of squaring numbers, the steps taken when creating a list are as follows.

- Initialize a list to store the results

- Iterate through the numbers and append the square of each number

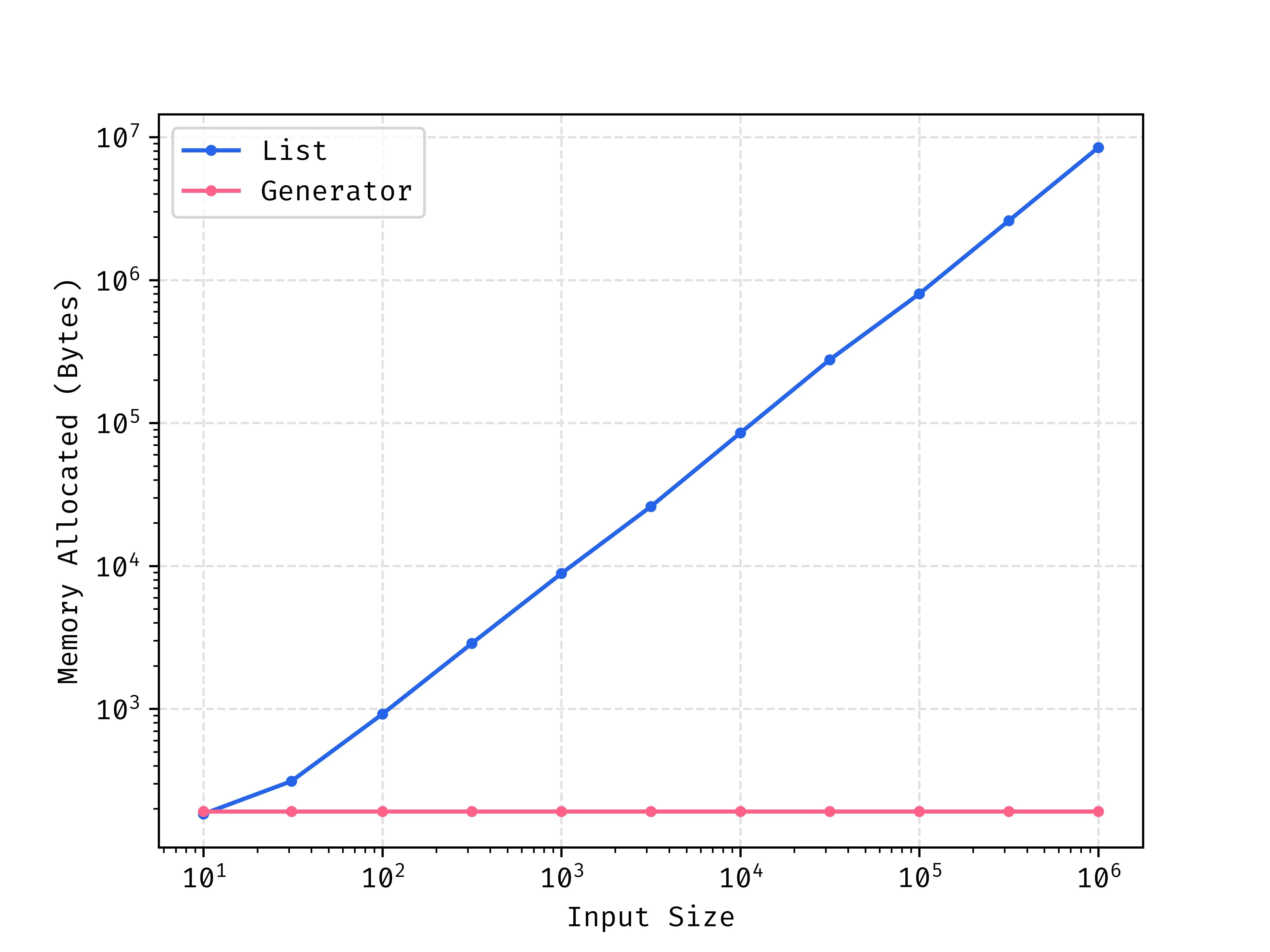

Seems simple enough! The issue is each number in our original list produces a square that has to be stored in the new list which can create a big memory problem. It’s easy to begin creating variations of an already large list and use up memory unnecessarily.

For our example, the generator would be an object that essentially evaluates “when I am called, I will iterate over the list of numbers and return the squared result for each number one at a time”. We never store all of the results at once, which is a good thing if you only need the results at runtime but not if you want to keep the results.

The below shows how memory usage changes with increasing input list size. The generator has a constant amount of space used as it only has to keep the process stored whereas the list variant has to store a larger and larger list that scales directly with input size.

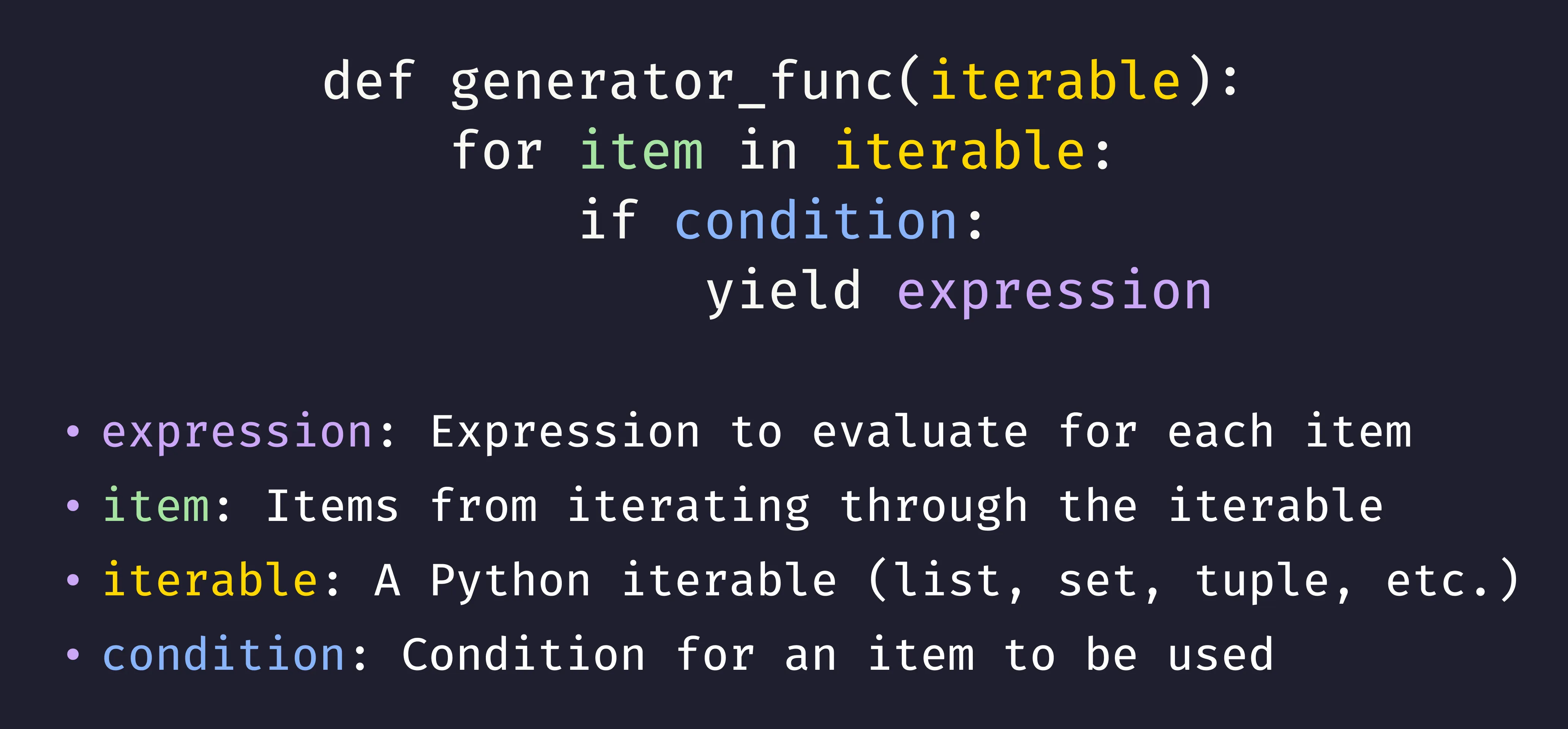

Generator via Loops

Let’s look at the basic structure of a generator based on our prior list examples.

You might say this looks similar to the list and you would be right! The differences are that the generator we’re interested in is actually the returned product of calling this function.

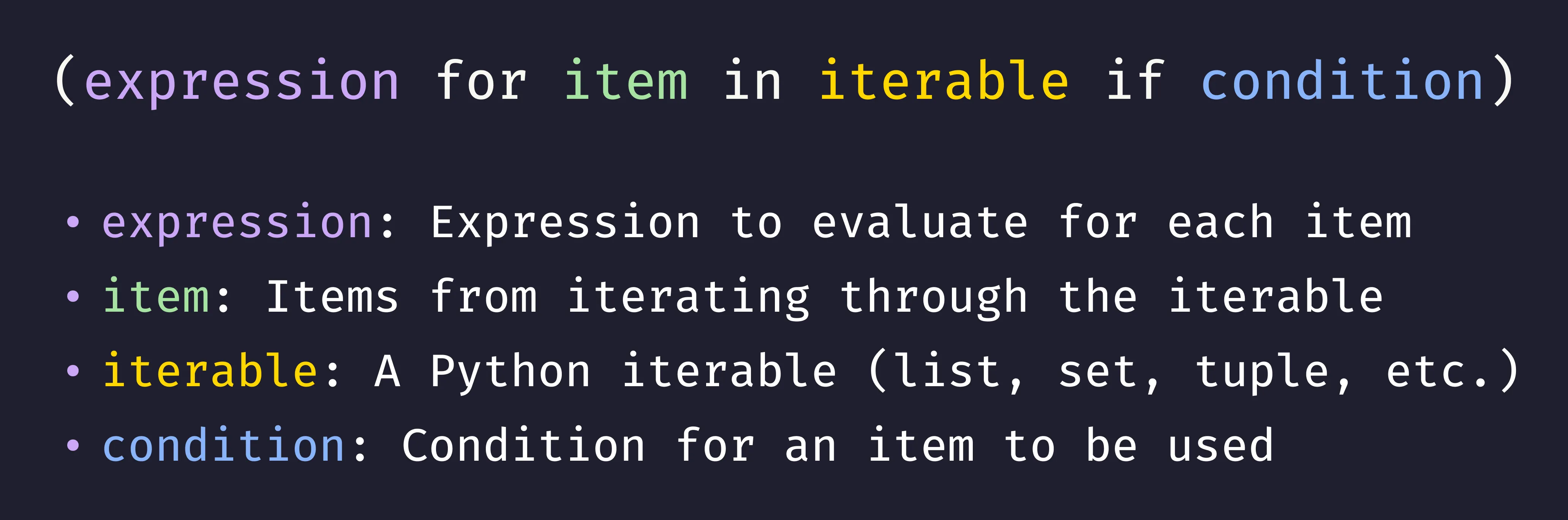

Generator via Comprehension

Phew that was a lot, luckily extending these concepts into a comprehension is trivial. All we need to do is replace the brackets from the list comprehensions with parentheses!

Examples

Let’s go through the same examples as before in the list section. One key difference that you’ll notice is that the generator itself does not have the resultant list stored. We have to call list on it to produce a list comprised of the generator results.

Squaring Numbers in an Iterable

We’re given an iterable of numbers and we’re asked to create a list of the squares.

# List of Numbers numbers = [-2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] # Iterative Generator def generator_func(numbers): for num in numbers: yield num ** 2 my_generator = generator_func(numbers) print(list(my_generator)) # Generator Comprehension my_generator = (num ** 2 for num in numbers) print(list(my_generator))

output[4, 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25] [4, 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

As expected we get the same result as the list comprehension but in practice if our lists were very large the generators can help us keep memory under control.

Flooring Floats

We’re given a different iterable full of floating point numbers and we wish to use floor to round down to the nearest integer, but only if the numbers are positive.

# Importing the floor function from math import floor # List of Numbers numbers = [0.15, 3.14, -5.8, 11.2] # Loop Variant def generator_func(numbers): for num in numbers: if num >= 0: yield floor(num) my_generator = generator_func(numbers) print(list(my_generator)) # Comprehension Variant my_generator = (floor(num) for num in numbers if num >= 0) print(list(my_generator))

output[0, 3, 11] [0, 3, 11]

Capitalizing Names

Given a list of names, create a new list where every name is capitalized.

# List of Names names = ["james", "charlotte", "Patrick", "elaine"] # Loop Variant def generator_func(names): for name in names: yield name.capitalize() my_generator = generator_func(names) print(list(my_generator)) # Comprehension Variant my_generator = (name.capitalize() for name in names) print(list(my_generator))

output['James', 'Charlotte', 'Patrick', 'Elaine'] ['James', 'Charlotte', 'Patrick', 'Elaine']

Set Comprehensions

Set comprehensions are ones that I often use and luckily they’re super simple as well!

Set Comprehensions as List Comprehensions

A set comprehension can be thought of as a list comprehension but the list is converted to a set after. As a reminder, a set is an unordered collection of items where no items can repeat.

# List => Set

# Native set comprehensions are faster but this is a good way of understanding

my_list = [num ** 2 for num in numbers]

my_set = set(my_list)Set Creation via Loops

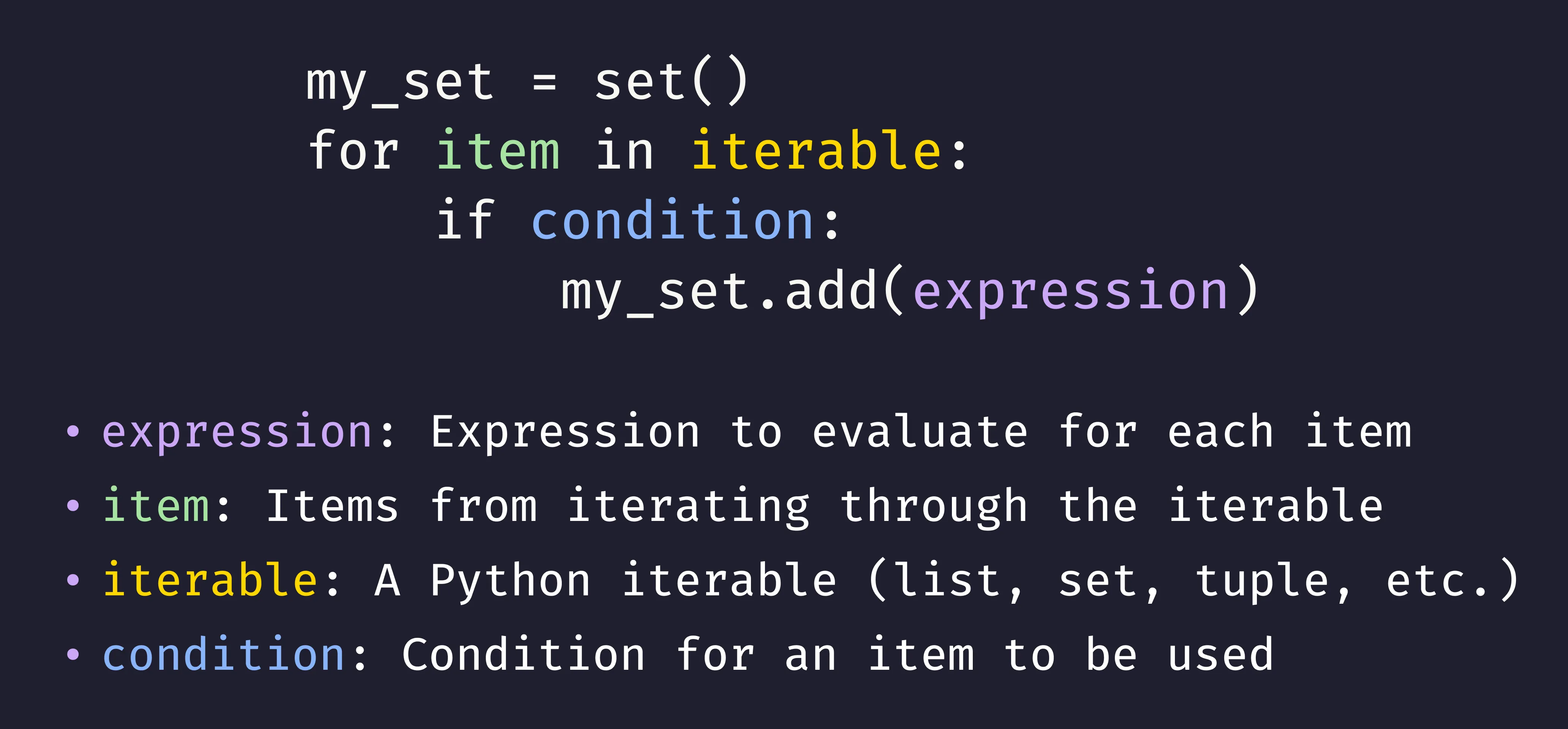

Following the theme of being similar to lists, you’ll see that the creation using loops is very similar. The only differences is initializing a set instead of a list using the add method.

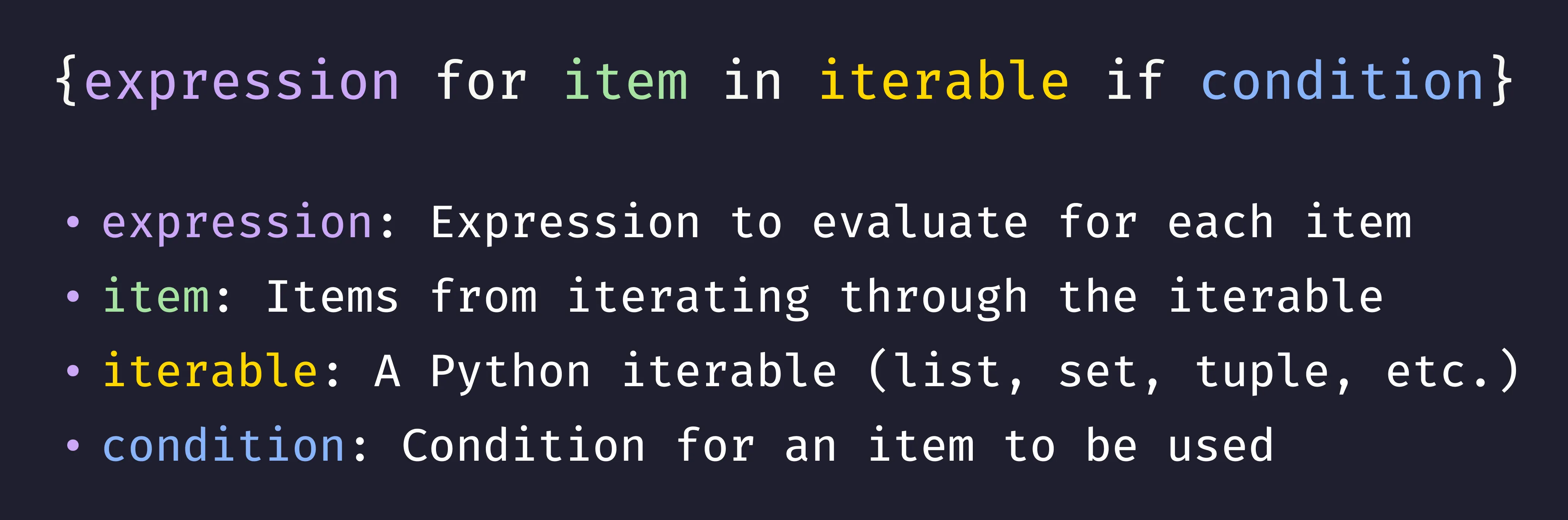

Set Creation via Comprehension

As you might expect, we just need to change the brackets to curly brackets.

Examples

Let’s go through the prior examples again but with sets!

Squaring Numbers in an Iterable

We’re given an iterable of numbers and we’re asked to create a list of the squares.

# List of Numbers numbers = [-2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] # Loop Variant my_set = set() for num in numbers: my_set.append(num ** 2) print(my_set) # Comprehension Variant my_set = {num ** 2 for num in numbers} print(my_set)

output{0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25} {0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25}

Note: -2 and 2 have a collision in this case, we only see 4 once!

Let’s go ahead and break down each of the important parts highlighted in the structure.

- Iterable: The iterable is the list

numbers - Item: Each number we retrieve out of the list is our item

- Expression: The expression is merely the squaring of the number

num ** 2

Dictionary Comprehensions

Dictionary comprehensions are mostly the same as prior examples but just a little different because we need to create not just an element in the collection but a pair of values.

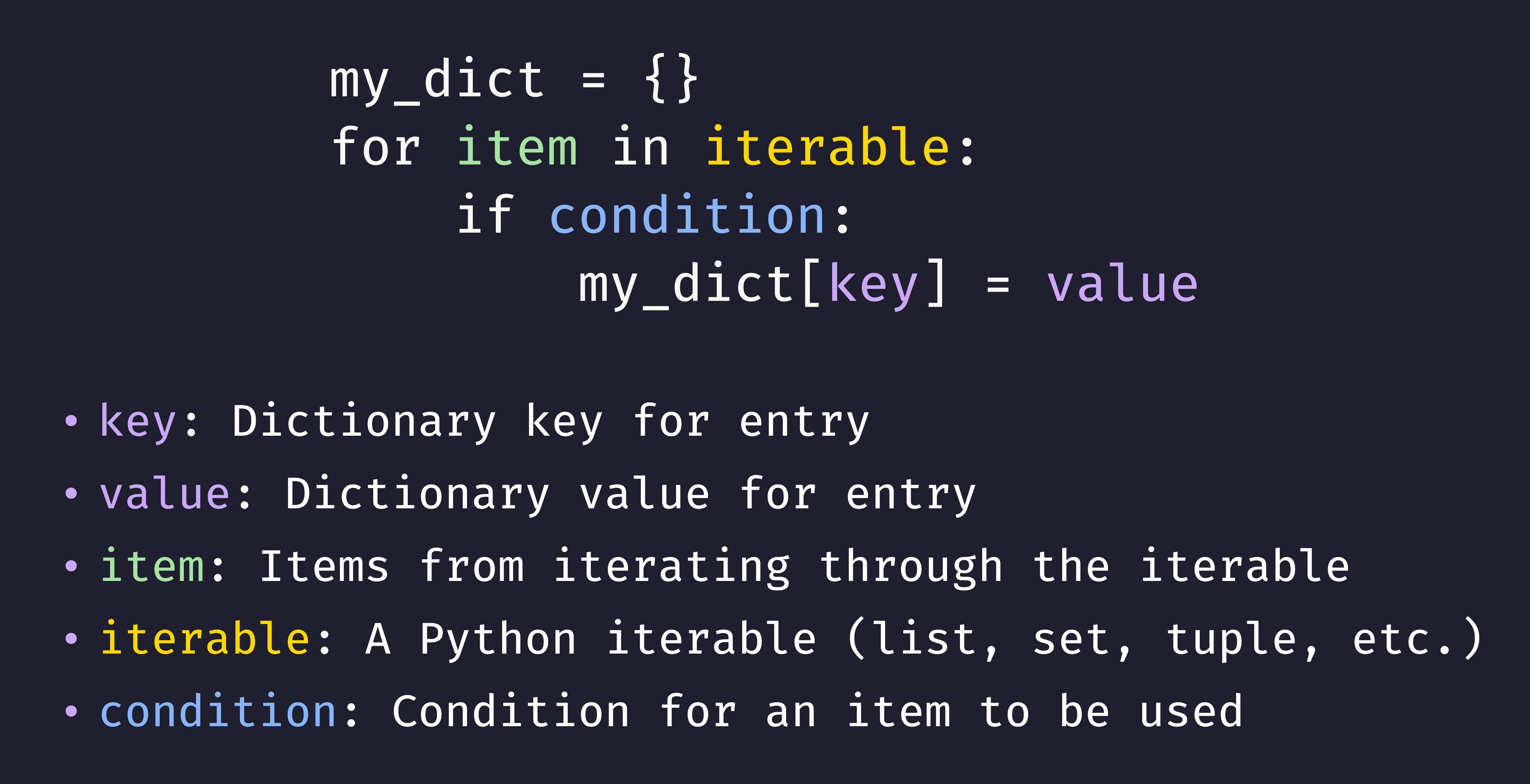

Dictionary Creation via Loops

It’s about what you would expect at this point where we do some sort of initialization, get items from out iterable, and run some code to define changes to our data structure.

You’ll notice that there are essentially two expressions that are based on the item, key and value! Often key will be the item or item id whereas value will be an expression.

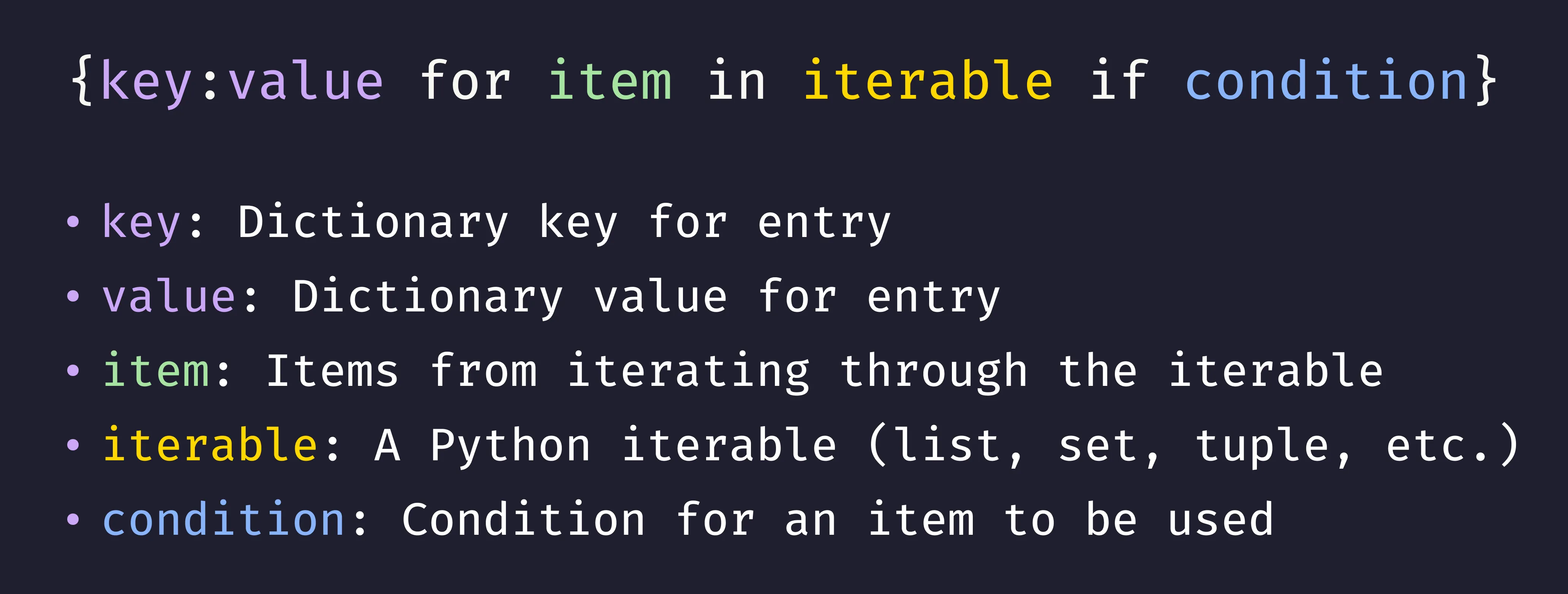

Dictionary Creation via Comprehension

The comprehension variant is similar to prior examples, but the expression is a pair of values, not a singular one. Note both set and dictionary comprehensions use curly brackets.

Examples

I will not be repeating the prior examples but I instead ones inspired by each prior example.

Squaring Numbers in an Iterable

We’ll square numbers but store the square as the value paired with the original as the key.

# List of Numbers numbers = [-2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] # Loop Variant my_dict = {} for num in numbers: my_dict[num] = num ** 2 print(my_dict) # Comprehension Variant my_dict = {num:num ** 2 for num in numbers} print(my_dict)

output{-2: 4, 0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25} {-2: 4, 0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25}

Flooring Floats

We’ll do a case where the key is the input number and value is the floored value.

# Importing the floor function from math import floor # List of Numbers numbers = [0.15, 3.14, -5.8, 11.2] # Loop Variant my_dict = {} for num in numbers: if num >= 0: my_dict[num] = floor(num) print(my_dict) # Comprehension Variant my_dict = {num:floor(num) for num in numbers if num >= 0} print(my_dict)

output{0.15: 0, 3.14: 3, 11.2: 11} {0.15: 0, 3.14: 3, 11.2: 11}

Capitalizing Names

Lastly, let’s used the capitalized names for the input keys and the value will be True if the name needed to be capitalized or false if it was capitalized already.

# List of Names names = ["james", "charlotte", "Patrick", "elaine"] # Loop Variant my_dict = {} for name in names: new_name = name.capitalize() my_dict[new_name] = name[0] != new_name[0] print(my_dict) # Comprehension Variant new_names = [name.capitalize() for name in names] my_dict = {new_name:name[0] != new_name[0] for name, new_name in zip(names, new_names)} print(my_dict)

output{'James': True, 'Charlotte': True, 'Patrick': False, 'Elaine': True} {'James': True, 'Charlotte': True, 'Patrick': False, 'Elaine': True}

I decided to end on a mixed example where I also used a list comprehension and zipping!

In this case, I didn’t want to have to capitalize the name twice in my comprehension (key side and value side) so I created a list of the capitalized names.

I then got out the pair of both original name and capitalized name using zip such that I could do the same thing as my iterative variant.

Closing

I hope you found this post informative and enjoyable! Comprehensions are some of my favorite bits of Python and I’m glad I got to share my understanding with you. Please let me know if anything didn’t make sense or any suggestions and I’d be happy to make changes.